What prompted man to experiment with original species and use artificial selection? What were the benefits of the agricultural revolutions? How did agriculture change with the advent of genetic engineering? What is the challenge of the third millennium? These are just some of the questions that Sergio Antolini seeks to answer in his book “Argonauta”, tackling his subject with historical rigour and taking the reader on a journey that combines mythology, philosophy, religion and science.

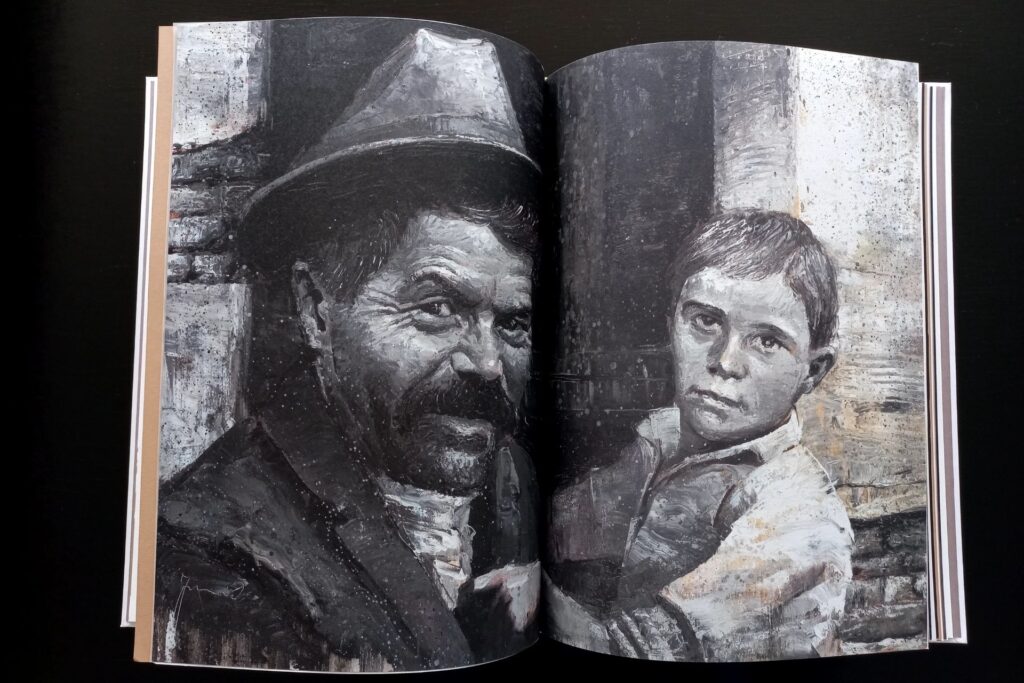

In a previous article taken from this book, Sergio Antolini explored the origins of wheat and showed how this important cereal led to the birth of a new civilisation, promoting human survival and population growth. It is a gripping story, told through a skilful combination of scientific aspects, cultural ideas and mythological references, including sources of knowledge that have either been lost or ignored. These include the great work of the agronomist and geneticist, Nazareno Strampelli, who experimented with a series of hybridisations in the 1920s, creating new plant varieties that increased crop yields and allowed Italy to drastically cut its grain imports. The historic “Senatore Cappelli” variety was selectively bred during that period and is greatly valued today.

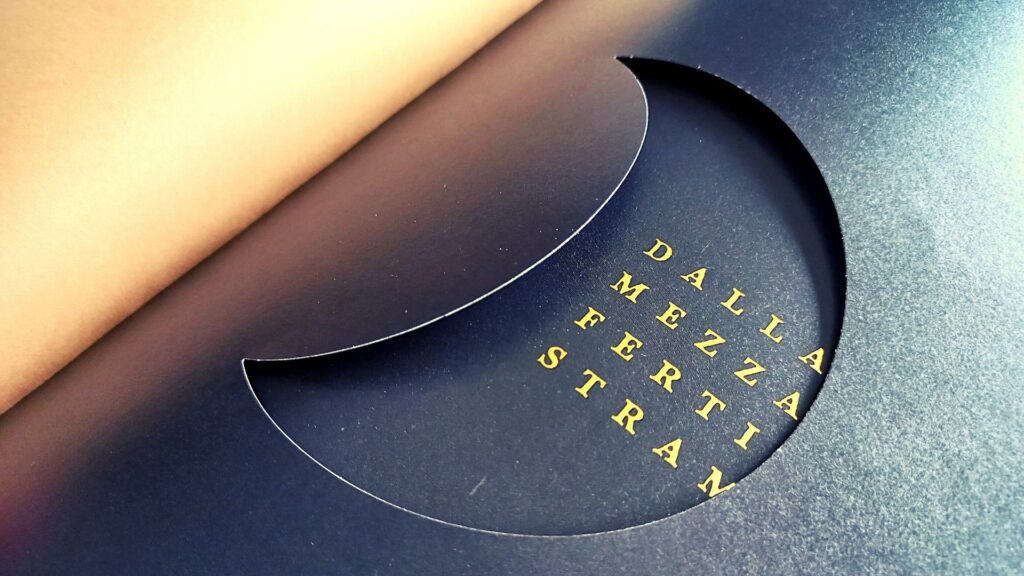

From Agricultural Revolutions To Sustainability

One particular thought from Sergio Antolini deserves a special mention: “Agriculture was the cornerstone of man’s evolutionary process, long before the invention of writing.” Research and innovation are not peculiar to the modern age, they have roots in the dim, distant past. Firstly, there was natural selection (as Charles Darwin taught us), and then the hard work and dedication of farmers. Later, this was followed by the input of agronomists, who helped make our agriculture a symbol of excellence and the envy of the whole world.

This goal was achieved through three agricultural revolutions. The first of these occurred in Neolithic times, when farmers chose to breed from those plants with certain desirable characteristics (e.g. larger fruits). The second dates from the early 20th century, when studies by the Bohemian monk Gregor Mendel led to the birth of the new science of genetics, and the task of selecting and hybridising plant varieties became the province of scientists and agronomic research centres. During this period, agriculture became increasingly mechanised, and fertilisers and pesticides came into common use. Finally, there was the Green Revolution of the 1960s to the 1980s, with the emergence of genetic engineering and an ability to “see” previously invisible characteristics through DNA sequencing. This led to modifications in plants which dramatically increased crop yields, allowing freedom from the scourge of famine for much of the global population.

Sergio Antolini takes an interesting and wide-ranging look at the role of man in influencing the laws of Nature, examining ideas from various cultures, from the Greek philosophers to the Judeo-Christian tradition, and taking us up to the Copernican revolution and the thoughts of Galileo, Descartes and Bacon. Although science and technology now dominate both man and nature, the hope is that science can contribute in a practical way, by making modern agriculture more sustainable and drastically reducing the use of chemicals. The real challenge of the third millennium.

The Milling Technique

“During the course of his physical and intellectual evolution, Man lost the strength of his jaw, relying instead on his brain-power.” Sergio Antolini uses this thought to introduce the sections about grinding and the introduction of rolling mills. The first rudimentary millstones date back to prehistoric times, and primitive crushing methods slowly evolved into proper grinding techniques. This continued until about 1850, when millstones reached their optimal state in terms of material, grooving, size and speed. At the end of the 16th century, the work of Agostino Rampelli led to the introduction of a new grinding process with the first example of an iron roller mill. However, this method did not become widespread until the mid-19th century when Friedrich Wegmann developed a better version of the roller process, enabling considerably greater production. From the early 20th century onward, grinding with millstones was abandoned in favour of the cylinder method, although it has made a recent comeback in a niche market dedicated to “forgotten” types of flour.

The Evolution of the Mill

The first examples of mills have been found in Persia, and date back to 3000 B.C. They were generally operated by slaves or, to a lesser extent, by animals. Later on, people exploited the power of water and mills were built along streams and rivers. The Greek historian Strabone (65 B.C.) writes about this practice, describing the vertical wheel mill. Later still, Vitruvius wrote an explanation of the gear transmission system, which has remained substantially unchanged up to the present day. In later times, alternative energy sources such as wind and steam were also used, making it possible to build mills in built-up areas, although such forms of power have now been supplanted by electricity.

For more information, or to purchase a copy of the book and the illustrations it contains, please contact:

Carla Gasperoni

Email: info@sa-intrl.com