The act of breaking and sharing a piece of bread is laden with meanings that bring together religions, cultures and strong social values. Sergio Antolini speaks about this in his book l’Argonauta, taking us along the long history of bread, on the discovery of this food which is both a humble food and a sacred symbol of human evolution.

The history of bread goes back centuries, rich in knowledge, poetry, art and faith. It embraces the entire evolution of mankind, it is the seal that connects the various cultures of the entire globe, whether peasants or princes, every kind of status. As we saw in the previous articles dedicated to the Argonauta, the book written by Sergio Antolini, the first bread making techniques already existed in the Neolithic. At that time the most commonly used grains were barley and millet, that man used to create the most ancient types of bread, unleavened bread, but we had to await the Egyptians (that Hecataeus of Miletus called “bread eaters”) for the development of leavened wheat bread, according the Mediterranean tradition. The ancient Greek were also expert bread makers, historians confirm their ability to make over seventy types of bread, using ingredients from spices to honey. The Romans did not have bread before meeting the Greek, their diet was based on “puls”, a type of millet polenta. But the Romans replaced the stone mill driven by slaves or animals with the mill driven by running water, producing dozens of types of bread. It was with the onset of Christianity that bread became the sacred food par excellence, through the Eucharist; bakers marked the sign of the cross on the loaf as a good omen for the person receiving it and for the person marking the sign. The tradition of personalising the bread by marking it with iron bars is found in various eras and cultures, the very Greek marked the bread to invoke the help of Demeter, the goddess.

In the entire history of mankind there has never been a food as important as bread, it brings with it memories, symbolic values, traditions, rituals and legends that go beyond simply nourishing the body, because bread also nourishes the spirit. And this is its special quality: it is both a food and a sign. “The poem of Gilgamesh, a Sumerian text from the second millennium B.C. recounts the process of civilising a wild man named Enkidu, who no longer limits himself to the consumption of beverages and food provided by nature, such as wild herbs, water, milk, but he begins to eat bread and prepared products that he discovers thanks to a woman who offers them to him”. Homer himself, in the Odyssey, says that “mortals are bread eaters, unlike animals whose diet has nothing civil, nothing intelligent“. The preparation of this food therefore becomes an emblem of human evolution and its relationship with religion and society, a symbol that unites the three great monotheistic doctrines – Christianity, Judaism and Islam – as well as an expression of messages of solidarity, brotherhood, love for others, sacrifice and friendship. According to Jewish law, the custom of breaking bread with your hands is emblematic, no knife is used because the cut recalls an idea of violence that is unacceptable for a food so rich in meaning. The preparation of this food in various shapes (geometric, anthropomorphic, floral, etc.) is still reserved today for festive and ceremonial events as a legacy of the ancient primitive offerings to the deities. The complex symbolism of bread is the backbone of all the rituals relating to the cycle of life (birth, initiation, marriage, death) and the year (sowing, cultivation, harvesting, harvest festivals). This is because in archaic societies life was conceived in terms of cycles, and wheat, which allowed one to make bread, was considered a sacred metaphor of this conception.

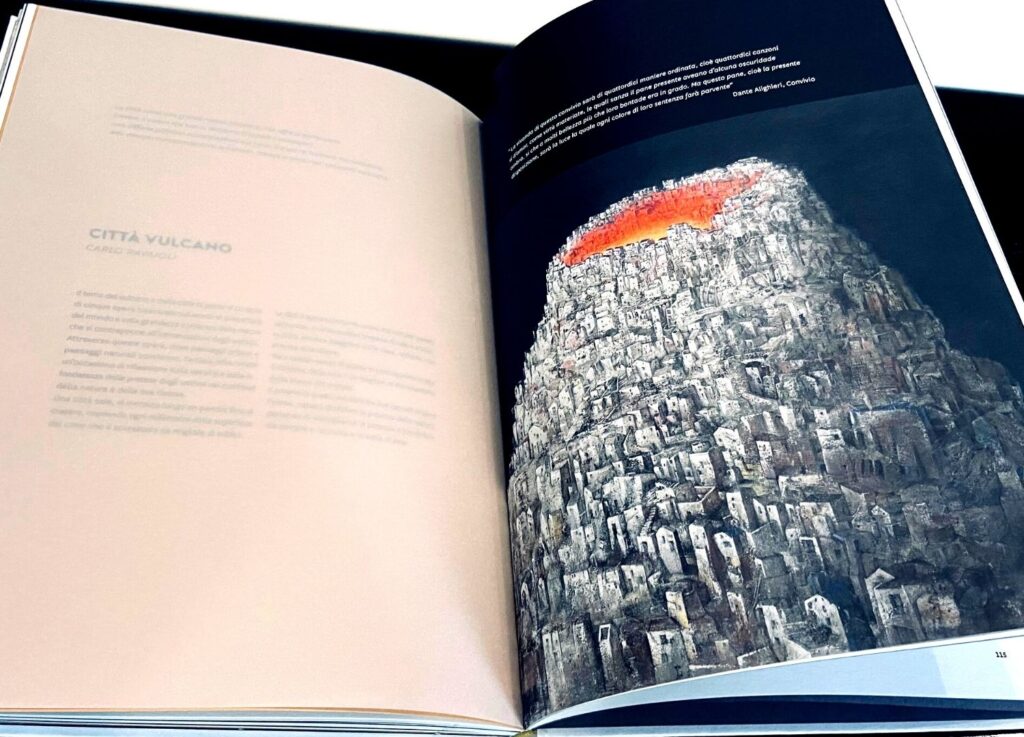

Bread, in its thousand varieties, is also found in many works of art, from ancient Egypt to pop art, as a cultural and religious sign of the different peoples who inhabit the earth, each with their own creed, their own custom and tradition. Different aspects united by the sense of sharing because, as Sergio Antolini reminds us, the origin of the term “companions” derives from the Latin “cum-panis“ i.e. those who eat the same bread and share life in joy, in work and also in suffering.

Bread, therefore, not only as a source of nourishment, but also as food to “take care of” to avoid wasting it, as our elders teach us who have invented tasty dishes made with stale bread. In respect of the many children, men and women who still suffer from hunger today.