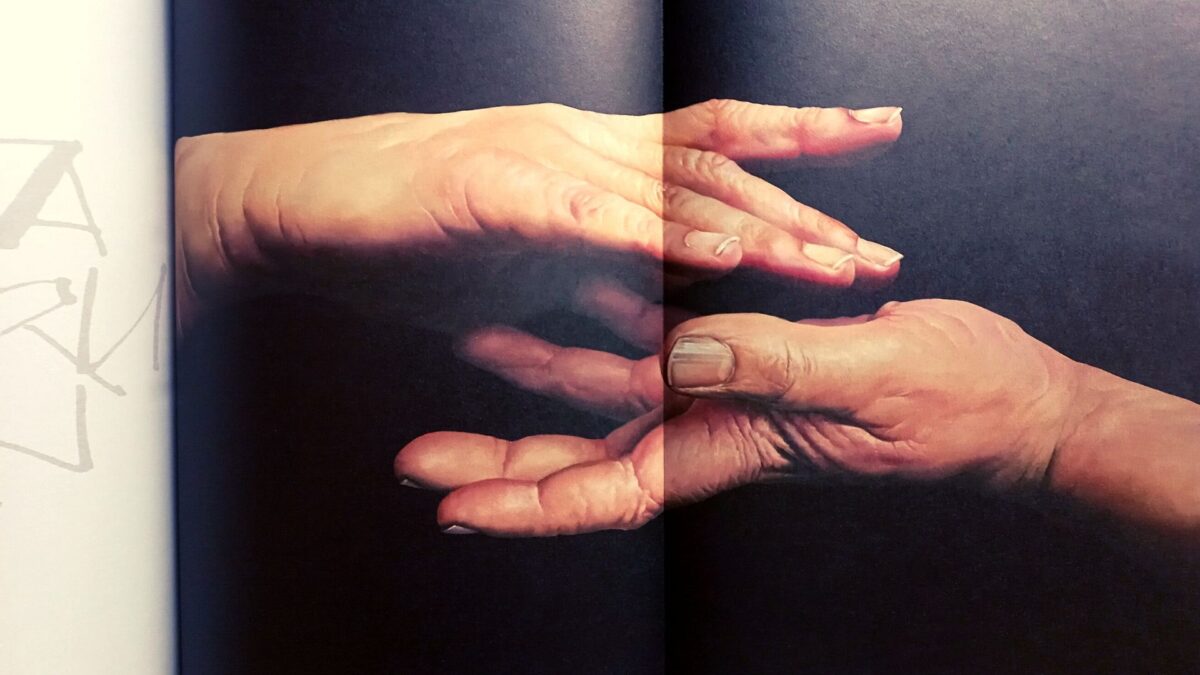

Browsing through “L’Argonauta”, it is interesting to find out how and when the figure of the miller was born. The miller makes an appearance at various points in history and his role is reflected in the living conditions of society at the time. He was envied by those who worked the land and given the blame during times of famine and shortages of bread. The miller also, however, gained experience and knowledge that could be passed down through the generations. His path in history was difficult and has often been given little recognition, but has led him to become an expert, sensitive and essential figure today. (Front cover: “Le Mani” by Filippo Manfroni).

L’Argonauta, a book by Sergio Antolini on the history and culture of wheat, is so packed with ideas and food for thought that we decided to share some other chapters with you. In previous articles we focused on the origins of wheat and the evolution of agriculture. Today we want to pay tribute to the figure of the miller that the author covered extensively, exploring the growth of this profession over a long period of time. Here is a quick recap. The first mills were operated by slaves, prisoners or animals and, in ancient Roman times, they belonged to the baker who was responsible for feeding the city and was appointed “Annona Officer”, the public official responsible for the procurement of foodstuffs. The socio-economic situation changed when slave labour began to run short and there are records dating back to the beginning of the 4th century, in the late Middle Ages, of the first workers involved in the production of flour at Arles. However, there was still no mention of the figure of the miller. He was in fact to emerge later, during the period of the Holy Roman Empire, when he assumed an important social role. The overlord entrusted him with a fief so that he could provide for his family, and in exchange he was to take care of the mill and the production of flour. Among all the artisans of the time he was the only one who enjoyed the privilege of being a (more or less) free man, and, through the practice of milling, he could acquire experience and technical expertise to pass on to his children. His status was tantamount to that of a member of the bourgeoisie.

Early Records

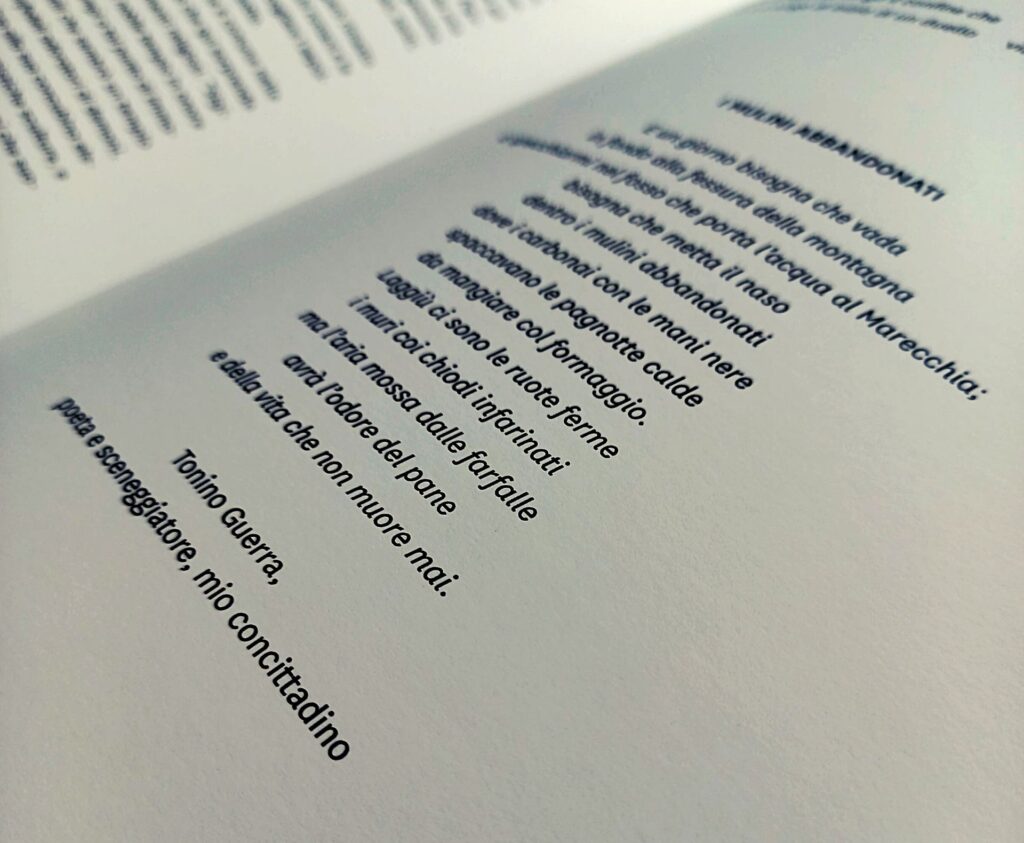

Manuscripts and iconographies dating back to the Middle Ages tell of how the relations between the miller and the overlord evolved: the latter entrusted the miller with the task of collecting dues from the peasants. Therefore the miller, despite being a “son of the people”, had a more comfortable living than many: in some cases he even owned the mill outright and could afford apprentices and servants. The miller received an income also from the wheat brought daily by the families of the fiefdom for milling; and with the use of a “sifter” (a sieve to separate flour from bran), the miller could further increase his profits. This privileged position caused resentment among the peasants and people who considered him a slacker and a thief, collecting 1/16 of the flour without doing anything, since the mill did the work. Relations between the miller and the ruling class placed him above the common people and for this reason he was shunned by society: he did not belong to any corporation, he was not attributed a patron, and the Church even considered him the devil incarnate because he was selling his own time, the prerogative of God alone. Within the confines of his isolation, however, the miller was able to refine his knowledge and acquire more experience which could be passed down through the generations. In the Renaissance, with refinement of the art, the figure of the miller was seen differently and the importance of the mill was recognised; indeed, the mill became an instrument of power disputed by the State and Church. The history of that period is preserved within the walls of the ancient mills, which have now become museums and a symbol of a technique, with the blades of a water mill, on the verge of dying out.

The Miller Of Our Times

The figure of the miller was finally seen in another light: as both craftsman and entrepreneur. Today the miller is the craftsman who knows how to recognise the quality of the raw material, the cereals he grinds; he is the craftsman who studies chemistry and biology to analyse the materials he uses and the products he creates; he is the craftsman with the mechanical and engineering skills required to operate the machinery correctly. Conversely, he is also the entrepreneur who knows the laws of the market and knows how to interpret the demand for ever new products; he is the entrepreneur who knows which flours to produce, and how; he is always the creator of a good product.

The figure of the miller has changed in keeping with the development of new tools: while once the craftsman relied on his own sight and touch, today the entrepreneur makes use of sophisticated equipment and innovative technologies, preserving an almost sacred aura bestowed by a timeless symbol: bread.

For more information, or to purchase a copy of the book and the illustrations it contains, please contact:

Carla Gasperoni – Email: info@sa-intrl.com