From boat mills on the river Po and ancient water wheels to modern roller mills. The city of Cremona played a major role in the art of milling, which has a longstanding tradition and, since the Middle Ages, has greatly influenced the culture and economy of this area of outstanding excellence. A never-ending story of farming know-how, brilliant ideas, and technological innovations that continues today, evolving into the modern Milling Hub.

From Boat Mills…

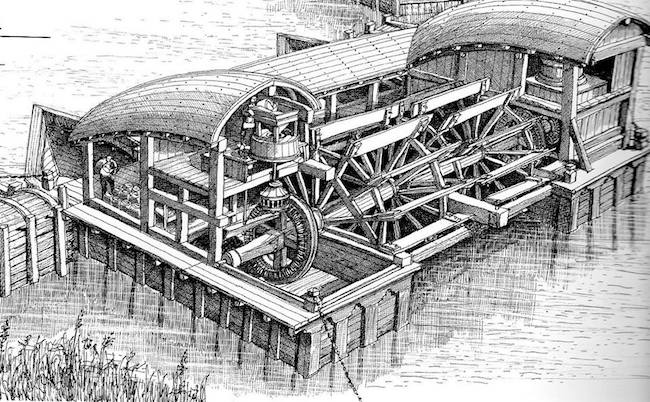

The history of the city of Cremona is closely linked to the Po river, Italy’s longest waterway, and to the complex surface water system, which allowed trade and the main business activities in the area to flourish. The art of milling emerged precisely because of this river: in fact, for many centuries, it was a very common activity in the area along the Po, providing sustenance for its people. The earliest proof of this dates back to the Middle Ages, when boat mills first appeared. They were huge machines, 12-13 metres long and approximately 11 metres wide, which were docked on the shore or anchored to the riverbed, in the section of the river with deep currents that flowed more quickly, by using large wicker or iron baskets that were filled with stones. In order to constantly exploit the motive force of water, even during seasonal changes in river water levels, the millers frequently shifted them along the riverbank or even from one side of the river to the other. The structure and mechanisms of the mills were entirely made of oak or walnut wood, since such materials were highly resistant to water, shocks and to the strong friction to which they were subjected. They were made up of two floating rafts with a flat keel. The sides and stern were almost vertical, with a raised bow, connected to each other by a wide deck and several chains. The stern had a paddle wheel mounted on a horizontal beam, which, by turning counterclockwise, set a series of cogwheels in motion, which then turned the stone millstone. Traditionally, there were two millstones, one for milling wheat and one for milling maize and other grains. Boat mills disappeared for good in the early 1900s when steam navigation was introduced, leaving leeway for boats and tugs.

…To Roller Mills…

The mills on land located near the millraces lasted a few more decades. Until the 1950s, the area around Cremona was filled with water mills, with their distinctive architecture. Each town had its own mill and, for many years, the life and economy of its residents centred around it. If the mill stopped, the people would starve and despair. A glimpse of reality that was masterfully celebrated by Riccardo Bacchelli, who wrote one of the greatest novels of 20th-century Italian neorealism: “Il mulino del Po” (The Mill on the Po). When, during the industrial revolution, steam mills became more powerful, more efficient and safer, hydraulic mills fell into disuse and, at the turn of the 20th century, were either phased out or converted to electrically driven mills. Meanwhile, technology was evolving rapidly in an effort to supersede the stone grinding system (in which the bran was not removed) by adopting a more efficient, uniform and hygienic method that involved the use of cylinders (roller mill). As we all know, the introduction of metal cylinders revolutionised the milling industry, which made it possible to separate the bran and crush the wheat into increasingly fine groats, thereby requiring less heat for the flour and processing the product in a hygienic and safe manner. From then on, the mills became what could be described as an industrial enterprise, and millers became expert food technologists. These days, when wandering through the countryside around Cremona, we can still see the remains of abandoned mills that are partially overgrown with vegetation or, in some cases, have been renovated by families boasting a long tradition of milling, flanked by modern mills.

Aside from a few rare mills that are still in operation, they have now become cultural assets, historical finds that are representative of important industrial archaeology. A kind of open-air museum where, by visiting the historic buildings, ancient millstones, metal paddle wheels (which are now rusty), grinding rooms and rustic porticos, visitors can take in the history of Cremona’s milling art. One of these latter examples is the location of Ocrim’s first plant, just outside the city, in Cavatigozzi, owned by the Grassi family who, right after the war, embarked on an extraordinary development project headed by “Captain” Guido Grassi.

…And the Milling Hub

Ever since then, technological progress has been steadily increasing, with a special focus on innovations based on brilliant ideas, supporting food businesses, monitoring the supply chain, and on sustainability, which can now be expressed in just two words: Milling Hub. The national milling hub that Ocrim designed and built together with Bonifiche Ferraresi, which opened last year, is located in the area of the Porto Canale (Canal Harbour) of Cremona, along the river Po, as if the baton was passed from the ancient floating mills that Ocrim pays tribute to with its reliability, experience and professionalism, which have been its hallmarks for more than 75 years.

Janello Torriani’s Invention

And speaking of brilliance, we would like to conclude this brief digression into the history of mills by mentioning another illustrious fellow citizen: Janello Torriani. He was one of the most renowned machine builders of the 16th century, a skilled blacksmith, a world famous clockmaker, hydraulic engineer, court mathematician and inventor. His father Gherardo owned half a boat mill and Janello, who watched him work, invented small automatic iron spring mills. This news was given by his friend Ambrosio de Morales, court historian to Philip II of Spain, who wrote: ‘Janello invented an iron mill that was so small it could be hidden in a sleeve. It could grind more than two measures of wheat a day and worked automatically, without anyone operating it. Another outstanding quality of this mill is that it separates flour from waste, which means that the purified flour falls into one bag and the waste into another. Such an invention could prove very useful for an army, or for a city under siege, or even for sailing, since it is an automatic mill.’

A set of seven portable iron mills, manufactured by Janello Torriani, was discovered in the collections of the Royal Palace of Madrid.

(Source: “Mulini: suggestioni di un mondo perduto” – Mills: impressions of a lost world; text by Liliana Ruggeri, photos by Antonio Barisani and Mino Piccolo, editor Cremona Produce)